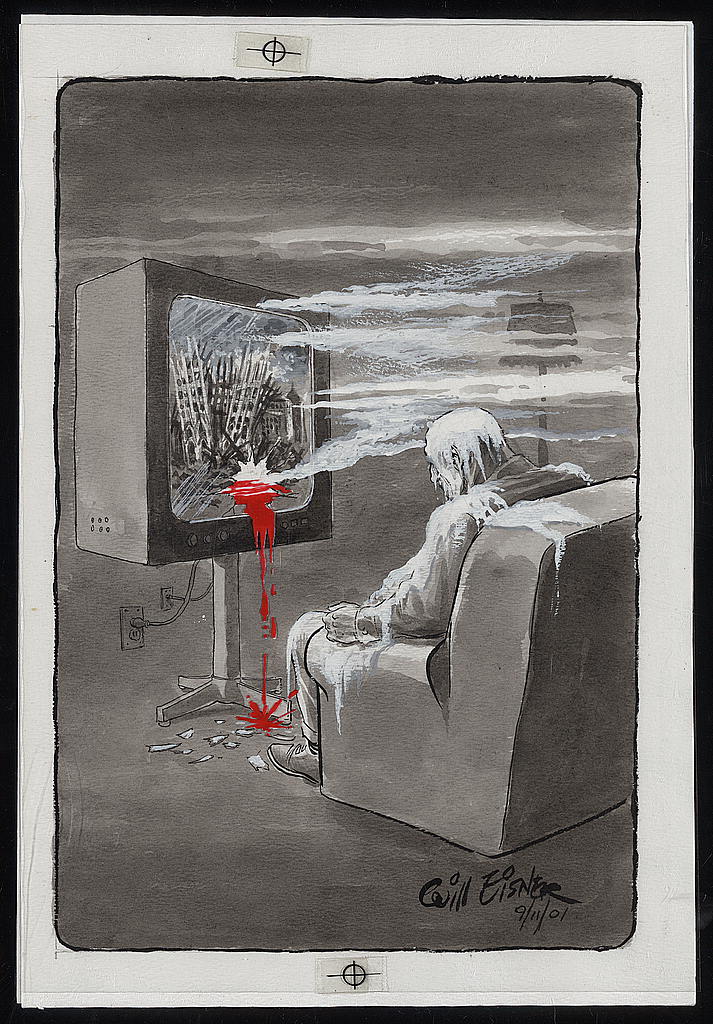

Will Eisner, Reality 9/11, ink, with red pigment mylar overlay, 2001. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Gift of Will Eisner.

When two planes destroyed the World Trade Center, another shattered the Pentagon, and one more crashed into a Shanksville, Pennsylvania field fifteen years ago I wasn’t a first responder, a member of the military or a family which had lost a loved one; I had no close connection with any of the more than three thousand people who died that day. Like so many others around the nation and the globe, I sat stunned and transfixed as the events played out on television, my heart and mind reeled from the attacks and my life changed dramatically.

At the time I served as Head Curator within the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. My office in the Madison Building looked out over the U.S. Capitol and I felt keenly my responsibilities for the safety of my colleagues and the security of the fourteen million historically significant objects for which we cared every day. The collections include many of our most culturally precious images while the staff I supervised and worked with comprises the most advanced professionals in the field, befitting the principal repository of knowledge in the free world.

As families, concerned citizens, medical and law enforcement personnel and public officials gathered at Ground Zero and in Shanksville following September 11th, 2001, to mourn and identify the victims, and begin recovery efforts, more terror ensued. On Capitol Hill we wondered if there were more attacks planned and instituted shelter-in-place measures to safeguard government workers. A week later, beginning September 18th attacks, envelopes containing anthrax spores were mailed to media offices and U.S. Senators in Florida, New Jersey and Washington, D.C., ultimately killing five people and infecting 17 others. On October 15th, after Senate aides opened letters containing weaponized spores, the halls of Congress were closed and federal workers told to stay home. The Library of Congress is connected to the House and Senate by tunnels, air vents, and a shared postal system; we also stayed home for a week until the buildings were finally cleared. I then went back to work, taking the Red Line subway back and forth daily from my home in Silver Spring, Maryland directly past the Brentwood postal mail facilities where technicians dressed in other-worldly haz-mat gear handled potentially poisonous packages. These days government workers are routinely ridiculed, stereotyped as lazy or incompetent, happy to feed from the public trough. In my experience, the vast majority are dedicated to public service and highly competent. In the days after 9/11 simply showing up to do your job became an act of courage.

I considered my role as a citizen and Federal worker paid by the American people. What could I, as a curator and librarian, do to address the situation? I recalled two episodes which helped frame my perspective. Before relocating to Washington, D.C. in 1991 to take up my new position at the Library of Congress I worked as Assistant Curator in the Print Room of the Boston Athenaeum, a distinguished private library on Beacon Hill in Boston, Massachusetts, founded in 1807. In 1865, following the Civil War, the institution sent two librarians south to collect books, prints, broadsides, correspondence and ephemera which otherwise would have been lost or dispersed amid the ruin and displaced lives caused by the conflict. Two hundred and fifty years later those materials are preserved at the Athenaeum and represent one of the nation’s largest extant collections of Confederate imprints, shedding invaluable light on that tumultuous time. During the late 1990s, after a visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I walked out of the building behind a young couple who had just viewed the exhibits. The man turned to his companion and explained that the despite what they had seen, he still considered the Holocaust a hoax.

In the meantime, while the nation’s capital hunkered down, New Yorkers rallied with public displays of patriotism and resilience. Numerous art galleries solicited their communities for images related to the events and expressing the range of emotions they inspired. Walls and sidewalks in Soho and Lower Manhattan were papered with thousands of photographs, prints and drawings documenting the environmental and emotional impact of the attacks. Hearing of these displays I wondered what would happen when the pop-up exhibitions ended. I spoke with my colleagues at the Library and determined to initiate a campaign to gather an archive of pictorial materials portraying not only what happened but how the nation responded. My managers, including Winston Tabb, Diane Kresh and Jeremy Adamson were incredibly supportive, while my fellow curators and colleagues within the Division of Prints and Photographs were eager to help: Helena Zinkham and Brett Carnell, Ford Peatross, Carol Johnson, Elena Millie, Katherine Blood, Sara Duke, Martha Kennedy, Verna Curtis, Maricia Battle and Beverly Brannan, among many others, all made contributions.

I met so many amazing people during the campaign who validated the initiative and inspired our effort. Photojournalist Bolivar Arrelano introduced me to a diverse and talented group of freelance Manhattan-based colleagues he represented including José Rivera, Steven Hirsch, Don Halasy, Tamara Beckwith and G.N. Miller, the latter a retired police officer whose images of the ruined towers are imbued with a grace and sensitivity worthy of photography’s great masters. Bolivar himself displayed unusual courage and dedication suffering injury by debris while photographing from the sidewalk below Tower Two as the second plane struck. Joel Meyerowitz, renowned for his evocative fine art compositions, spent months at Ground Zero amidst the rubble and crews working there to recover bodies and remove the shattered piles. Illustrator Maira Kalman and Rick Meyerowitz, Joel’s brother, donated preparatory sketches and a finished print of “New Yorkistan,” a comic cover for The New Yorker, which appeared on the December 10th issue and signaled that the city’s legendary sense of humor had returned to the fight against fear. Eminent graphic designer Karen Simon created an iconic image, “Rise Above,” which embodied the notion that following terrorists into the abyss might lead us to our own demise. Helen Zughaib’s paintings beautifully expressed the human commonality of Americans and Muslims in the Middle East, offering a heartfelt alternative narrative. Editorial cartoonists, comic creators and political illustrators were among the first to portray the attacks and their impact. We acquired original art produced by Will Eisner, Garry Trudeau, Alex Ross, Paul Levitz, Ann Telnaes, Tony Auth, Kevin Kallaugher, Sue Coe, Peter Kuper and many others. Printmakers soon followed and the archive includes portfolios and individual prints created by artists at Pyramid Atlantic, the Corcoran School of Art, the Washington Printmakers Alliance, and Manhattan Graphics Center. We acquired numerous whole collections: with the assistance of Jeanette Ingberman of Exit Art we brought in thousands of images she solicited from around the globe and dozens of original artworks published in graphic art anthologies issued by DC Comics and Alternative Comics. These examples represent a small sampling of highlights preserved in the 9/11 archive.

In September 2002 the Library mounted an anniversary exhibition featuring dozens of works we acquired along with newspapers, maps and other 9/11 related materials compiled throughout the previous year. The exhibition is captured online within the Library of Congress website and the Online Catalog of the Prints and Photographs Division now includes scans and catalog entries for hundreds of photographs, prints, cartoons, illustrations, and posters from the era.

The effort compromised my physical and mental well-being. My mind processed everything I saw and the images stay with me, resurrected with every anniversary. The painful memories are compounded by the death of my mother from a long fight with cancer; she died in a Boston hospital on September 30th, 2001, the chaos at Ground Zero and elsewhere a searing backdrop to her suffering. I can’t recall one without remembering the other. A pictorial anthology published after the attacks likened the fall of the World Trade Center to losing a parent and the convergence of tragedy deepened my despair.

Ultimately, however, the archive was worth it. We gathered thousands of images for the national collections which otherwise would have been lost or dispersed. They show how these horrific events occurred and the subsequent impact they made on our collective psyche. Preserved for posterity, this body of visual evidence will help guide future generations toward a fuller understanding of the toll inflicted by the 9/11 attacks.