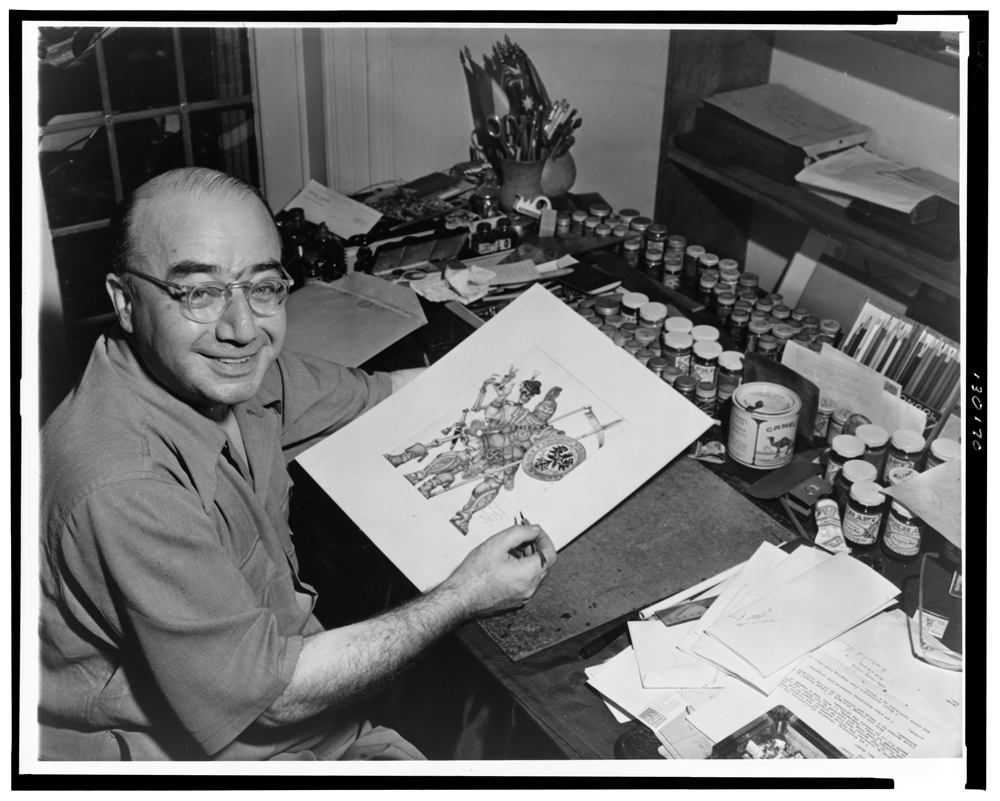

Arthur Szyk in his Studio

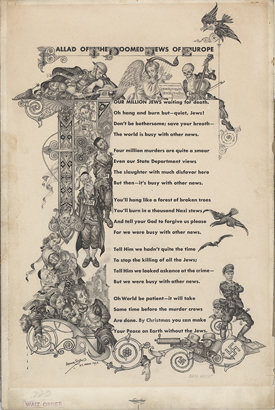

Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe, 1943

Twenty years ago, when I first became familiar with Arthur Szyk’s art, he was under-appreciated by museums and the marketplace. While generations of Jewish families at Passover routinely read from his internationally popular illuminated version of The Haggadah, and rare book connoisseurs coveted his lushly illustrated and elegantly bound special editions, the details of his life and body of work were largely overlooked outside a small community of collectors, curators and scholars in the field of Judaica. Szyk collectors were isolated, disconnected geographically and intellectually. He appeared to have separate reputations in disparate fields: Judaica, war art, book design, and illumination; few understood or recognized the totality of his efforts.

The Internet has transformed interest in his career, offering new scholarship and commentary, dedicated websites and online sales records; an overview of information and images, and a global net connecting Szyk enthusiasts and collectors around the world. A growing list of articles, books and exhibitions, documentary films and symposia examining his contributions as fine artist and graphic activist has helped raise his profile as scholars and admirers explore the unique qualities found in his art.

Szyk’s original illustrations and illuminations typically exist as exquisite masterworks from which poured a fountain of books and prints, articles and essays, posters and pamphlets. Most were created for reproduction, but Szyk always labored to ensure his originals were so precisely executed that reproduction would not diminish their visual impact. Nonetheless, it is in the colors, compositions, and carefully delineated details that Szyk’s illustrations shine; his graceful line and sharply penned caricatures appear more vivid in the flesh.

Szyk’s career witnessed several phases and numerous plateaus; in Poland, Paris, London, Canada and, finally, the United States. His early Polish works reflect an unformed illustrative style based on a variety of contemporary influences including French posters á la Toulouse-Lautrec and Cheret, and Steinlen, among others, or the German satirical cartoonists of Simplicissimus. The first of Szyk’s political drawings appeared in Poland with the onset of WWI, sketchy line drawings revealing a mordant wit and populist sensibility.

Engaged in the war as a soldier and propaganda artist, Szyk’s career went on hold, only to be reinvigorated and reinvented in Paris during the 1920s. Embedded in the cultural center of the Western world, Szyk pursued his path toward a mature style, at once seemingly inspired and repelled by Cubism, Dadaism, German Expressionism, Primitivism and other modern art movements. Leaning on Old World values in contravention of the new, he turned to medieval illumination and Byzantine design, inherently abstract traditions which made Szyk’s paintings seem at once fresh, iconic and timeless.

Over the course of a decade, Szyk tightened up his technique and realized his vision. His pen and ink roundel portraying “Moses” (1918), suggests his more integrated approach to illustration. Two illustrations, “Ivan Tsarevitch et le Loup Garou” (1920) and “David and Saul” (1921) indicate his progression, creating life-like tableaus framed or overlaid with allegorical elements and attributes, achieving an intricate synthesis of iconography and design. His triptych entitled “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam” (1923) depicted scenes of Jewish persecution, a prelude to his Statutes and clever spin on fifteenth-century Dutch realism. The only triptych Szyk ever created, it represents yet another milestone in his development as an artist and social commentator.

Szyk soon learned to apply colors as if they were jewels, luminescent and hard-edged. “Shulamith and King Solomon” (1925) is a magnificent expression of Szyk’s newfound confidence and maturity; infused with life as if Szyk cannot quite contain his brush the figures threaten to burst their bounds. Two additional works, “The Queen of Sheba before Solomon” (1927) and “Suzanne et les Deux Vieillards” (1927), represent the culmination of this phase. These lavish Biblical illustrations are highly polished, the figures lushly modeled within an abstract fabric formed of equal parts ornament and perspective. Pre-cursors to his celebrated series of illuminated portraits, they number among his finest creations from a particularly fertile and formative period.

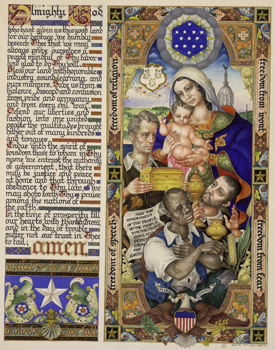

Four Freedoms Prayer (1949)

Szyk reached new heights internationally during the 1930s with the publication of two momentous works, The Statutes of Kalisz (1932) and Washington and His Times (1932. Hitler’s rise compelled Szyk back into the political arena where he applied his shrewd intellect and unique technical skills to expose the Nazi menace. No one was better prepared to portray the madness overtaking Europe and the world. Szyk had seen such carnage before and created inspirational images spurring men to fight. He knew how to rally troops, mobilize citizens, demonize and demoralize the enemy.

He drew up a storm of provocative images for publication in Great Britain and North America creating an illustrated timeline of evil. Szyk’s drawings appeared regularly, repeatedly, in popular magazines and journals as covers, inside illustrations, and advertisements. They were a wakeup call for citizens deadened by a decade of hard times, sheltered by an ocean and largely unresponsive to the atrocities playing out across Europe. Szyk’s often vividly colored and viciously rendered satires made fools of Nazi leaders and their Fascist followers at home and abroad. His grotesque caricatures of Axis leaders pounded a graphic drumbeat driving the nation’s war effort. Always meticulous and thoughtful, Szyk’s worldly perspective and stunning technique produced political illustrations with their own intrinsic value as works of art.

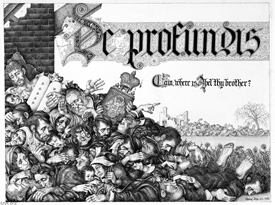

First among them must be “De Profundis” (1943), Szyk’s haunting Holocaust tour de force. In my thirty years’ experience looking at political art, I have never experienced its equal. You cannot “unsee” this image, it calls to mind Goya’s scathing anti-war etchings, Raemaker’s lurid drawings, and Kollwitz’s anguished, Expressionist woodcuts and lithographs. The personal passion and professional purpose driving “De Profundis” are extraordinary, Szyk endows this damning statement with grace and beauty worthy of the dead. It was his burden as a Jew, his gift as an artist. “De Profundis” was not conceived with retrospection but created spontaneously in the midst of war as reports surfaced of Holocaust atrocities and Allied victory seemed a distant dream. Distributed widely in the U.S. by the Textbook Commission, in an effort to combat anti-Semitism, Szyk went well beyond his remit, confronting readers with an image designed to sear their eyes and scour their souls. Recently, “De Profundis” (1943), was paired with Marc Chagall’s pre-war lament, “White Crucifixion” (1938), to spark a discussion within Catholic scholarly circles regarding Holocaust responsibility.

Ben Hecht’s collaboration with Szyk in “Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe” (1943) came just months after reports of the Holocaust first surfaced in the United States. Screenwriter and committed Zionist Ben Hecht’s searing stanzas savaged Christians and blaming the United States State Department for ignoring the situation, while Szyk provided a grim framework of Jewish victims. The illuminated ballad proved controversial, raising eyebrows and awareness with its caustic conclusion: “By Christmas you can make Your Peace on Earth without the Jews.” The original illumination bears an ink stamp reading “Wait Order,” documenting the delay in publication. A truly momentous piece of American Judaica which, when paired with “De Profundis,” represents a last-ditch, back-handed effort to stir up empathy and action on behalf of Europe’s doomed Jews.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in spring 1943, on the other hand, offered Szyk an opportunity to commemorate Jews as heroes not victims, portraying the doomed defenders as willing martyrs dedicated to self-defense and armed resistance. The figures depicted in “The Repulsed Attack – Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto” (1943) are not faceless, they are recognizable individuals known to have participated in the fight. Two years later Szyk followed up this pen and ink sketch with “Samson in the Ghetto” (1945), an extraordinary painting created in the flush of Allied victory. After WWII, as the fight for a Jewish homeland intensified, Szyk’s iconic images of citizen-soldiers helped lift morale, raise awareness and bolster the Nazi resistance.

Drawings which comprise Szyk’s two war-time compilations, The New Order (1941) and Ink & Blood (1946), number among his most popular images and valuable works. Some reveal personal associations. For example, “We’re Running Short of Jews” (1943) bears the inscription, “To the memory of my darling Mother, murdered by the Germans somewhere in the Ghettos of Poland…” Szyk matched his description as a “soldier in art,” employing every weapon in his arsenal, even his own personal tragedy, to fight the Axis and win the war.

Szyk produced his late masterpiece, “Thomas Jefferson’s Oath” (1951) while under scrutiny for his membership in “subversive” organizations named by the U.S. Congress. Most were dedicated to the support of Jewish refugees and Israel. He responded with masterworks of patriotic art expressing his enormous faith in American values, even as those in power questioned his allegiance. Illuminating Jefferson’s words, Szyk challenges the House Un-American Activities Committee investigations: “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” Below, Saint George, wearing the uniform of a U.S. Army soldier, fights the dragon of tyranny, a call to action for Americans perhaps made complacent by peace and prosperity.

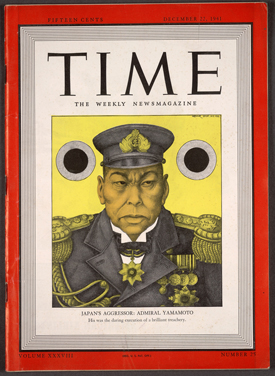

Admiral Yamamoto, Time Magazine, 1941

One of Szyk’s last paintings, it is also one of his best, capturing a moment in American history when a global conflict of bombs and bullets had ended and a new Cold War of words and ideas begun. Szyk intended his historical illuminations to decorate homes and schools, guiding citizens back to time-tested virtues and values, stressing good government, responsible citizenship, and global cooperation. The notion of America captured Szyk’s imagination like no other country. A committed internationalist, he saw the United States as a leader in the world’s new order, a place “where freedom lived.”

Szyk first signaled his interest in the United States in the late 1920s, within his illuminated edition of the Statute of Kalisz, a thirteenth-century document granting unprecedented rights to Polish Jews. Szyk biographer Joseph Ansell has characterized Szyk’s Statute as the artist’s reentry into the political life of his native Poland after a decade of expatriate life in Paris. Szyk clearly admired the United States Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Declaration of Independence as effective blueprints for providing and safeguarding civil liberties and personal freedoms for Jews around the world. He embellished his English translation of the Statute with imagery derived from the American flag, including portraits of Poles – Casimir Pulaski and Haym Salomon – who helped liberate Americans from British rule. Szyk’s Statute was but his initial effort to remake the Old World politics of Europe into his vision of the New World created in the United States.

Between 1929 and 1932 Szyk conceived and executed an ambitious tribute to the American legacy of democracy and freedom: a series of thirty-eight watercolor miniatures entitled Washington and His Times. Comprising a visual history of the American Revolution, the series included portraits of such military, political, and popular heroes as General Washington, Paul Revere, Benjamin Franklin and John Paul Jones, along with their European compatriots, the Comtes de Lafayette and Rochambeau of France, Thaddeus Kociuszko and Kasimir Pulaski of Poland, Johann De Kalb and Baron Von Steuben of Germany. He depicted such momentous events and significant scenes as the Boston Massacre and the Battle of Bunker Hill, Washington Crossing the Delaware, the battles of Trenton and Princeton, Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Moultrie, Valley Forge, and the surrenders of Burgoyne and Cornwallis. Through this series Szyk sought to bring these historical figures and events once more into focus for a modern world threatened by multiple modes of social and political repression and economic depression. The American experience during and since the Revolution appeared to him a vital, successful model of a free, democratic society. The publisher, Max Jaffé of Vienna, included an explanatory preface which reads in part:

Mr. Szyk has made no attempt to picture a scene realistically, or to recreate it as it may actually have occurred. He has chosen, rather, from the vantage ground of time and artistic insight, to interpret the life and significance of Washington by a series of portraits and scenes in which he expresses the philosophy he finds beneath the surface of familiar events. It is a treatment of history which necessitates the use of symbols and conventions and demands an active rather than a passive appreciation.

Mr. Szyk maintains that an essential purpose of art is the expression of ideas and ideals which have governed the development of the human race, and hence, as is natural, he has devoted himself untiringly to historic and traditional subjects, stressing the themes of peace and freedom. The series of paintings which is reproduced for the first time in this portfolio was conceived as a tribute to the memory of Washington and the events in which he figured, offered by the Old World to the New.

First exhibited in Paris in 1931 at the Exposition Coloniale Interpavilion and subsequently in Geneva at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, the series was published in 1932, the bicentennial of Washington’s birth. Although at the time Szyk, after a decade of expatriate life in France, still considered Paris his home, the Polish government sponsored a traveling exhibition devoted exclusively to his work, signaling extraordinary national pride in his achievements and an eagerness to exploit his art as an effective vehicle for official foreign policy and international relations. During 1932 the artist and his works appeared in cities and towns throughout Poland. In 1933, the government sent Szyk and the show to England to promote toleration and combat anti-Semitism then rampant in Europe, and to showcase the creative accomplishment of a prodigal native son. By the end of the year the exhibition, with the artist and his wife Julia in tow, was embarked on a tour of the United States, opening at the Brooklyn Museum. Supported by the Polish government and the Federation of Polish Jews in America, the exhibition was praised as both a symbol of Jewish cultural achievement and a manifestation of Polish solidarity with American values.

During the exhibition’s run in Washington, D.C. at the Library of Congress, U.S. Congressman Sol Bloom awarded Szyk the George Washington Medal in honor of his contributions to the recent bicentennial celebrations of the first American president’s birthday. The series of miniatures reached an even wider audience through its publication and dissemination as a portfolio of reproductive prints in England and America. Following a subsequent venue in Cincinnati and a second show in New York City the Szyks returned to Poland in summer 1934 after a seven-month visit to America. In early 1935 the Polish government purchased the Washington series from the artist and presented it to President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a gift of the Polish people. Displayed in the FDR White House for many years, the original watercolor miniatures now reside in the Roosevelt presidential library at Hyde Park, New York. Szyk’s high-minded efforts to express his vision of freedom and liberty as core values for Jews and non-Jews in Poland and America, and around the world, resonated at the highest administrative levels in both countries.

The social, economic, and political conditions he found in the United States during this initial visit made a powerful, positive impression on Arthur Szyk. Only his wife’s demurral due to the oppressive summer heat they encountered in New York City banished thoughts of immediate emigration to America. Arthur and Julia returned to Europe, where he devoted himself to the prodigious and prolific production of illustrations offering portraits and allegories depicting a vital, empowered Jewry unified in the face of growing fascism and anti-Semitism.

The next few years, spent largely in London, were consumed by his creation of an illuminated Haggadah, a landmark in the history of illustrated books for which he is justly celebrated. Szyk introduced into his remarkable rendering of this venerable, traditional Jewish prayer book images and symbols drawn from contemporary Jewish life: Nazi swastikas, modern ghetto residents, Zionist settlers in Palestine. His new illuminations invigorated the old text, revitalizing the Haggadah story of Jewish liberation from Pharoahic repression, alluding in no uncertain terms to the current plight of European Jews.

De Profundis, 1943

While living in London between 1937 and 1940, Szyk further proclaimed his strong affection for America in a series of twenty-three miniatures entitled, The Glorious Days of the Polish-American Fraternity, recalling for his countrymen across the globe the deep affinity he perceived between the American and Polish people, their shared struggle to create governments supporting civil liberties and religious tolerance. Commissioned by the Polish government for the 1939 World’s Fair held in New York City, the series portrayed the numerous individuals and events which symbolized to Szyk the historic bonds between the two nations, from the apocryphal landing of “the half mythical” Polish explorer John Kolna on the American coast in 1476, sixteen years before Columbus, through the numerous and notable contributions of Polish military personnel during the Revolution, to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s dramatic call for Polish independence in his Fourteen Points proclamation of 1918, issued in the aftermath of World War I. The prefatory text to a twenty-postcard souvenir portfolio of the series cited President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s comments upon the 50th anniversary of General Vladimir Krzyanowski, Commander of the “Polish Legion” in the Union Army during the American Civil War:

Throughout centuries and storms, no matter if the sun was shining or obscured by temporary clouds Poland forever fought to carry high the light of Liberty. As we treasure in common the same idea of Liberty, our friendship with Poland was longstanding and uninterrupted. It is an honour and a privilege to bear witness how the U.S.A. is indebted to people of Polish blood. We acknowledge the merit of the fearless heroes, fighting for liberty, of Kociuszko and Pulaski, whose very names became the watchwords of freedom. Their feats form an immortal chapter in the history of American freedom.

Following the 1939 invasion of Poland by Germany Szyk, still living in London, was increasingly sought after to produce drawings and satires in support of the Allied war effort. His anti-fascist, and specifically anti-Nazi, stance was known throughout Europe; also, he had experience as a soldier and artist during World War I, creating graphic satires and inspirational art and serving in the Polish armed forces.

In London, he produced exhibitions of war drawings for the English government. In summer 1940 he left Europe for the British Commonwealth nation of Canada with his family, remaining there for six months to inspire the war effort, explaining, “When we work for Britain, we work for our own country. Britain is the only stronghold of democracy in Europe.” By late 1940, the Szyks were in New York to stay, as biographer Joseph Ansell reports, “He was on a mission, partly at the request of the British and the Poles but mostly a self-appointed one, to alert and inform the Americans about the gravity of the situation in Europe.” An entire year would elapse before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor impelled America into the global conflict, nonetheless Szyk did his part early and often to compel Americans to join in the fight.

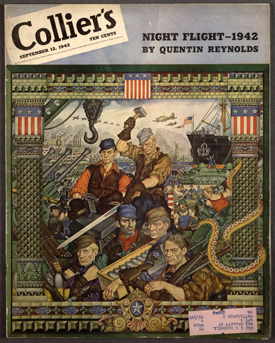

He developed exhibitions of war drawings, cartoons, and caricatures for galleries in New York, Washington, and San Francisco. His art garnered praise wherever it appeared. Szyk was everywhere in America during the war years, developing exhibitions of original works and producing illustrations for reproduction in such leading American newspapers and magazines as The New York Post, The Chicago Sun, The American Mercury, Collier’s, Esquire, PM, and Time. His numerous covers for Collier’s, one of America’s most popular magazines, were bold and colorful, inspiring devotion to the Allies or fear and loathing for the Axis. Time embellished its cover with his chilling caricature of Japanese admiral Yamamoto, architect of the aerial assault on Pearl Harbor, just days after the event shook the nation to its core. Each month from February through August 1942 the journal featured a large, colorful and dramatic new Szyk war cartoon.

During World War II, Arthur Szyk delineated for Americans the vicious face of European and Asian militarism and fascism as frequently and effectively as any artist anywhere. His work was demonstrably different from other artists and cartoonists across America, more ubiquitous and visible in America and Western Europe than that of such celebrated contemporaries as George Grosz, by 1940 a New York City resident and past his glory days, or John Heartfeld, the great Soviet propagandist. Yet he spawned no imitators, no school of Szyk; perhaps his art was born of too much knowledge, passion, devotion, skill and sacrifice.

His detailed, Byzantine, medieval style and meticulous technique contrasted dramatically with the simpler gestural line drawings typical of American cartoonists and illustrators. In Europe his work finds echoes in the war drawings of the Dutch cartoonist Louis Raemaekers or the Polish illustrator Wladislaw Benda, but in America Szyk was without peer. Editorial cartoonists in America were led by the likes of Ding Darling, Rollin Kirby, and Herbert Block (aka “Herblock,” the same cartoonist who labeled “McCarthyism” and gave Richard Nixon hell for fifty years). Norman Rockwell was in his prime, and a new generation of graphic humorists, including Saul Steinberg and even Ted Geisel (better known as “Dr. Seuss”), were producing war-related work.

Szyk, Arsenal of Democracy, Collier’s Magazine, 1942

Rollin Kirby, whose career spanned the two world wars, warned Americans of Hitler’s rise in the early 1930s while Ding Darling’s cartoons epitomized the enthusiastic, patriotic, “can do” attitude taken by mainstream Americans toward involvement in the war. Herblock helped turn the tide of American public opinion from isolationism to interventionism, winning the first of four Pulitzer Prizes for his early war work. Ted Geisel’s recently rediscovered cartoons for PM, a progressive daily paper published in New York City which also featured Szyk’s drawings, represent a gentler, more comic take on a terrible time. Saul Steinberg, at the outset of his brilliant career as the nation’s most influential conceptual cartoonist, produced a number of humorous and telling satires of Axis leaders. He caricatured Hitler as a witless dunce unable to draw a proper swastika. He depicted Stalin standing next to a gas pump telling Hitler “the gas is very expensive around here, about 10,000 Nazi to the gallon.” Stylistically, Steinberg comes as close to Szyk as anyone in America. His satirical portrayal of Axis leaders in “The New Order” offers an effective example for comparison with Szyk’s more detailed, colorful, and menacing treatment of the same subject.

Norman Rockwell’s design for a poster illustrating The Four Freedoms (Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, Freedom from Fear, Freedom of Speech), articulated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his 1941 State of the Union address, offers yet another point of comparison with Arthur Szyk’s American work. In his own rendering of The Four Freedoms Prayer, Szyk produced an exquisitely intimate and moving image, markedly different from the far more monumental and realistic designs painted by Rockwell for posters commissioned by the Saturday Evening Post. Small in size, Szyk’s Prayer is nonetheless a dramatic, coherent, and unified composition conveying the emotional intensity and spiritual depth of a Renaissance piéta. In comparison, Rockwell’s designs for posters illustrating the Four Freedoms provoked Ben Shahn’s remark that they treated Americans “as if they were twelve years old.” During World War II, Rockwell’s “pictures for the American people” depicted people who were almost exclusively middle class and white, Jews were rarely seen and blacks virtually nonexistent. His impulse toward diversity appeared only decades later as race riots and demonstrations consumed American cities during the Civil Rights Era.

Szyk’s American contemporaries lagged behind him in their awareness of and concern for social justice and civil liberties, even in their own country, which he had so recently adopted. Two cartoons from the 1940s offer harsh commentary on racism in America. In a 1944 sketch he depicts two GIs, one white and one black, conversing while guarding German prisoners of war. The white soldier asks his black counterpart, “And [what] would you do with Hitler?” The black GI responds acidly, “I would have made him a Negro and dropped him somewhere in the USA.” Several years later, in 1949, a year in which the Tuskegee Institute reported three lynchings to the NAACP, Szyk drew a cartoon depicting a black man bound and on his knees, watched over by armed, robed, and hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan. Above his head appears the caption, “Do not forgive them oh Lord for they do know what they do!” Inscribed below is an additional caption in Szyk’s hand which reads, “Each Negro lynching is a national disaster, is a stab in the back to our government in its desperate struggle for Democracy.” Searing images with captions like these rarely appeared in mainstream American publications. Among nationally syndicated American editorial cartoonists only Herblock and, later, Bill Mauldin and Jules Feiffer, addressed the nation’s race problem with the commitment and sensitivity revealed in Szyk’s work.

Arthur Szyk’s killing pace of production – he died too young at age 57 – slowed but never faltered after the end of World War II. He refocused his sights on the welfare of Jewish Holocaust survivors, the emerging Israeli state, and the ongoing fight to safeguard in America the civil liberties and tolerant atmosphere so many had fought and died to preserve. The post-war years in the United States were overshadowed by palpable fears of nuclear warfare and Congressional investigations into the “un-American” activities of Communist Party members and sympathizers.

In spite of his remarkable, unstinting and indefatigable contributions to the Allied war effort and his self-proclaimed status as “Roosevelt’s soldier in art,” Szyk came under suspicion as a Communist fellow traveler in the last few years of his life. His name appears repeatedly in reports compiled and issued by the Committee on Un-American Activities of the United States House of Representatives. In the HUAC report released in April 1949 he is listed as a member of numerous “subversive” and Communist-sponsored groups and committees: the Win-the-Peace Conference, the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, the American Slav Congress, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, the Peoples Radio Foundation, Inc., the Committee for Free Political Advocacy, for example. On these lists his name appears with other notable American artists, writers, stage and screen performers, and public figures including Langston Hughes, Rockwell Kent, Paul Robeson, Artie Shaw, Leonard Bernstein, Marc Blitzstein, Nicolai Cikovsky, Aaron Copland, W.E.B. DuBois, Philip Evergood, Albert Einstein, Howard Fast, Robert Gwathmey, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Jose Ferrer, Judy Holiday, Crockett Johnson, Ring Lardner, Norman Mailer, Thomas Mann, Arthur Miller, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edward Weston, John Sloan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Dehn, Max Weber, Studs Terkel, Jacob Lawrence, Paul Strand, Linus Pauling, and Isaac Stern. The list goes on.

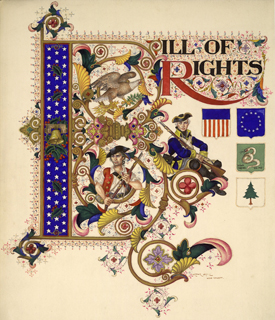

The Bill of Rights (1949)

It probably did not comfort Szyk that he was in such astonishingly good company. Roosevelt was dead and the worldwide war of bombs and bullets gave way to a new global conflict of ideas and ideology. With the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s the meaning of patriotism and sacrifice in America shifted as a new generation of politicians came to power. The fact that Szyk produced during this last troubled period in his life some of the most patriotic, eloquent, and important examples of twentieth-century graphic art ever created in the United States – his illuminated Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights, and Four Freedoms Prayer – only heightens the irony and pathos of his late career. His “Declaration of Independence,” completed in 1950, is a spectacular masterpiece of artistic detail and historical allegory, positively glowing with sincerity and passion. Below the illumination Szyk inscribed these words: “To my fellow Americans, I dedicate with love this immortal heritage of our forefathers. May these words live in our hearts forever and ever, for no good man loses his freedom but with his life . . .” Was it physical ailments from a difficult life and profoundly exhausting mission that killed him, or the irony of embracing a country which to him symbolized freedom only to find shackles of the mind and spirit he could never have imagined would appear in a free democracy?

In the end, Arthur Szyk was unique in his artistry, his mission, and his message. No wonder his art looks so different. He had fought as a soldier and knew first-hand the horrors of war. He had lost his mother Eugenia to a Nazi death camp and personally confronted the bottomless depths of racial rage. Isolated by oceans and sheltered from warfare no American artist was so utterly prepared as he to fight the tyranny of hearts and minds he found everywhere in his travels through Europe and even North America, where he dreamed freedom lived. He brought all of his terrible knowledge and experience to bear in his art, like Dorian Gray painting a collective portrait of evil presented daily to a world at war. He was democracy’s weapon, a soldier in art wielding pen and brush to render the face of racial hatred and social injustice, its horrid features intact for all to see. His postwar masterpieces, in contrast, are transcendent, reminding Americans of the ideals upon which their government was founded, their shared values and common capacity for warmth, compassion, tolerance and understanding.

SOURCES:

The Arthur Szyk Society: szyk.org

Katja Widmann and Johannes Zechner. Arthur Szyk : Drawing against National Socialism and Terror. Berlin: Deutsches Historisches Museum, 2008

Ansell, Joseph P. Arthur Szyk: Artist, Jew, Pole. Oxford and Portland, OR: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. 2004

Luckert, Steven. The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk. Washington: The United States Holocaust Museum. 2003

Irvin Ungar, Curator. Justice Illuminated: The Art of Arthur Szyk. Burlingame, CA: Historicana. 1998

Katz, Harry L. and Sara W. Duke, Curators. Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom. Washington: Library of Congress. 2000. Go to http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/szyk/

Minear, Richard H. Dr. Seuss Goes to War. New York: The New Press. 1999.

Hennessey, Maureen Hart and Anne Knutson. Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People. New York: Abrams. 1999

For original cartoons by Arthur Szyk, Herb Block, Ding Darling, Rollin Kirby, and Saul Steinberg, and other World War II-era American cartoonists go to the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog at: http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/catalog.html