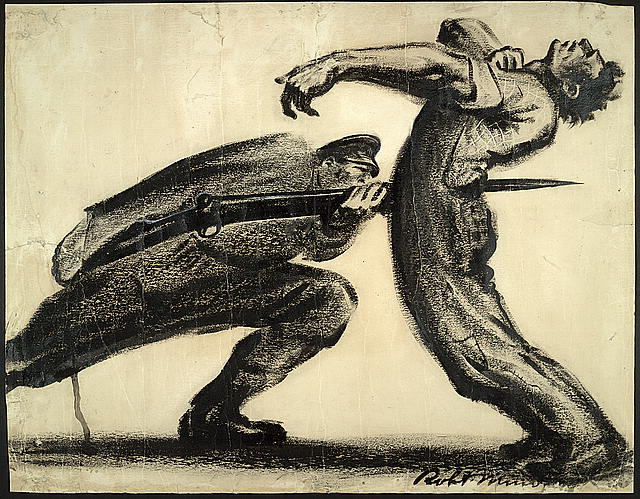

Robert Minor, Pittsburgh 1916, lithographic crayon on paper, 1916

Nineteenth-century French artist and political activist Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) never set foot in the United States but his influence has been pervasive. The rabble-rousing caricatures and political illustrations he created during the 1830s defended republican virtues and attacked the compromise king Louis-Phillipe, his court cronies and legislative louts.

Following decades of Revolutionary and Imperial rule, The July Uprising in 1830 brought the French monarchy back to power. In the streets things went from bad to worse as resentment and resistance toward the crown turned violent. The situation was resolved temporarily in 1848 when armed rebellion ended the July Monarchy and ushered in the short-lived Second Republic which lasted just until 1851, when President Louis-Napoléon organized a successful coup and proclaimed himself Emperor.

For a few years, between 1830 and 1835, censorship rules were relaxed by an apparently grateful King Louis-Phillipe. In 1831, following his self-education in art and an informal printmaking apprenticeship, Daumier signed on with provocative publisher Charles Phillipon’s new satirical journal, La Caricature. The next few years defined Daumier’s character and career. He created royal caricatures and political prints which attacked the motives and fundamental decency of the monarchy. In 1832, he was jailed for six-months for his cartoon assault on His Majesty and his minions, in particular “Gargantua” (1831), which presented Louis-Phillippe as a gluttonous behemoth feeding off the people.

Undaunted, Daumier continued the crusade, in 1834 once more provoking official wrath with two iconic masterpieces of political art: “Le Ventre législatif” (The Legislative Belly) and “Rue Transnonain,” granting him immortal status with Goya, Hogarth, and Gillray. The Frenchman’s painterly effects and controversial views were forcefully displayed in “Rue Transnonain. Le 15 Avril 1834 “ (1834), his revolutionary graphic attack on governmental oppression which depicted a scene from the deadly suppression of silk workers in Lyon by municipal authorities. The King could only take so much and, not surprisingly, new censorship restrictions soon ensued; in 1835 he banned political cartoons from French publications.

In response, Phillipon folded La Caricature and shifted to social satire in a new journal called Le Charivari. Daumier quickly settled into his role as the world’s most gifted graphic satirist, leaving the barricades to a younger generation while continuing to skewer French society and human nature with uncanny insight and empathy. Over the course of his life he created more than four thousand artworks including prints, drawings, paintings and sculpture.

The new medium of lithography powered Daumier’s inventions and enabled his artistic vision. Invented by Alois Senefelder in Germany in 1796, within decades the innovative printmaking process became a common medium among fine and commercial artists, admired as a remarkably inexpensive and expressive means of creating art for publication and reproduction.

Freed from the engraver’s burin artists could for the first time reproduce painterly brush strokes on the lithographer’s stone to create atmospheric landscapes, penetrating portraits and political cartoons sliced from current events and offered for sale within days. The flexible new method proved more fluid and forgiving than such conventional intaglio processes as etchings, mezzotints and stipple engravings. Daumier soon mastered the stone, producing figures fully modeled and full of life. He became the brightest star in the galaxy of French cartoonists who transformed the way cartoon art was perceived by the public. Phillipon’s group included artists of enormous talent and gravitas including Gustave Doré, Paul Gavarni, André Gill and André Grévin, Grandville, Henri Monnier and Nadar (who later pioneered the art of portrait photography). It is no wonder that the landmark nineteenth-century English comic journal, Punch, openly proclaimed itself, “The London Charivari.”

Daumier’s Paris was the kind of city many Americans yearned for, cosmopolitan and cultured. His cartoons showcased the modern French bourgeoisie, the merchants, mechanics, mid-level clerics and lawyers who reflected, even in the fun-house mirror of his art, the aspirations and ambitions of a new middle class; a development people in the United States were already experiencing for themselves. He was democratic in his opinions and his art, ridiculing the masses with affectionate guile while saving his bitterest bile for enemies of the people. Honest outrage and technical facility armed his art and doomed his victims to graphic infamy.

In America, beginning in the 1840s, Daumier’s art found an early echo in the art of political illustrators creating cartoons for popular political lithographs issued by Currier & Ives and other firms. An 1848 cartoon entitled “An Available Candidate,” published by Nathaniel Currier of New York — future famed printmaking partner of James Merritt Ives – features an American general suspiciously similar to Mexican war hero Zachary Taylor (who won election as US president in 1848 on the strength of his military exploits). The Currier print depicts a uniformed candidate seated atop a pile of skulls, alluding to the penchant of American voters for leaders tested in battle and steeped in warfare. The simple composition and clear message departed from British precedents and defied popular pro-war and expansionist sentiment, drawing rather from Daumier’s graphic vision, technical facility and provocative ant-establishment politics.

Winslow Homer began his immortal career in the 1850s as a lithographer’s apprentice in Boston. He shared the city’s early and influential admiration for French art. His singular print entitled “Arguments of the Chivalry” (1856), portrays South Carolina legislator Preston Brooks’ vicious assault on Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a visual foreshadowing of the impending Civil War. Known from a single extant impression preserved at the Library of Congress, Homer’s tour-de-force derives from Daumier’s bold technical and stylistic innovations. Generations later, editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant, a Daumier disciple wrote:

What a wonderful medium is lithography! The range and subtlety of the middle tones. The deep, velvety blacks. What a visual treat!

Although they were drawn for the moment, these works survive as art, even if one is unaware of the issues and the subject matter. It is the consummate artistry and the draftsmanship that we are left to admire. You seem to have been able to imbue every drawing, lithograph and painting with an urgent, surging sense of movement. (from Washington Post, February 20, 2000. pG8)

The Daumier echo became a crescendo after 1900 when Robert Minor, Boardman Robinson, John Sloan and other radical leftist artists directly applied his lessons and lithographic crayon directly to paper, creating some of the most powerful and provocative editorial images in the history of American art. Minor’s visceral portrayal of a Pittsburgh labor strike in 1916, published in the landmark Socialist journal, The Masses, set the tone in its horrific depiction of a steel worker bayonetted by a policeman.

Such politically explosive illustrations led to the demise of The Masses, forced to cease publication by U.S. postal authorities for its pre-World War I pacifistic stance. Legendary Washington Post Herbert Block (“Herblock”) picked up the mantle in the 1930s as the Great Depression enfolded America and fascist militarism loomed in Europe. Herblock started out in 1929 as an adherent to the pervasive Midwestern school of editorial cartooning, a pen-and-ink, generally genial style associated with John McCutcheon, Ding Darling and others. By 1934, with Hitler in power and Spanish Fascists threatening republican rule in Spain, Herblock’s warm humor and cartoonish pen increasingly gave way to bold swaths of crayon, forming a denser, darker vision of the world and life in the United States. Edmund Duffy, Daniel Fitzpatrick and others followed his path, infusing their daily cartoons with graphic seriousness and substance hitherto rarely encountered in mainstream American newspapers. More recently, such cartooning legends as Bill Mauldin and Pat Oliphant have given master classes in effective cartooning, empowered by Daumier’s legacy of bold imagery, biting caricature and trenchant provocative commentary.

There are those among the current crop of political cartoonists who, with Oliphant, continue looking to Daumier for inspiration. Jeff Danziger is a fine example. Daumier’s expressiveness lives on in their work, his legacy of artistry and activism fueling the fires of their outrage and ongoing efforts to confront readers and those in power with an alternative perspective.