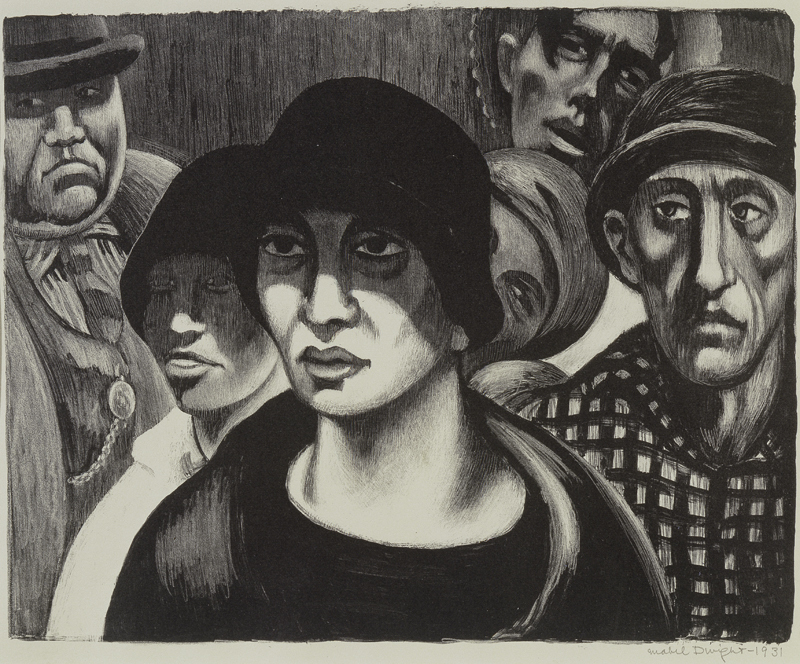

Mabel Dwight, In the Crowd, lithograph, 1931. Library of Congress.

This is pre-eminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper.

So first of all let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance . . . Happiness lies not in the mere possession of money, it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.

The joy and moral stimulation of work no longer must be forgotten in the mad chase of evanescent profits. These dark days will be worth all they cost us if they teach us that our true destiny is not to be ministered unto but to minister to ourselves and to our fellow-men. . .

Inaugural Speech of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Given in Washington, DC, Saturday, March 4th, 1933[1]

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, uniquely among American Commanders-in-Chief, understood the civilizing power of the creative arts at a time when the civilized world was imperiled and made desperate by economic upheaval and global social and political strife. During his first administration, the New Deal policies he established the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project which, between the years of 1936 and 1942 paid American artists to produce works of art on paper illustrating the life they observed every day in towns, cities, homes, streets, neighborhoods and more rural environments. The purpose was two-fold: to inspire and encourage the economically and spiritually depressed multitudes through fine art, while gainfully employing and capturing the creative talents of the nation’s artistic community.

The thirties were desperate times. Issues were clear: life and death, war and peace, poverty and plenty, education and ignorance. Conflicts appeared overwhelming and seemingly insoluble: labor vs. management, black vs. white, fascism vs. freedom, Capitalism vs. Communism. Artists became more socially aware and responsible. Printmaker Mabel Dwight described the change and sounded the charge: “Art has turned militant. It forms unions, carries banners, sits down uninvited, and gets underfoot. Social justice is its battle cry. War, dictators, labor troubles, housing problems all appear on canvas and paper.” A new communal sense of purpose developed among artists, particularly printmakers.[2]

The printmaking world had already begun a stunning transformation in the twenties, well before war and depression accelerated the process. Prior to World War I traditional print processes held sway in the fine art marketplace. Change, however, was in the air. Artistic lithography gained adherents, popularized by Daumier and Manet, and such great European poster artists as Cheret and Toulouse-Lautrec. George Bellows and Charles Locke, among others, led the way for American artists working in lithography, while woodcuts and wood engravings created by German expressionists and English traditionalists respectively, witnessed a revival.

Content also underwent a makeover. Led by artists inspired by social or political, rather than aesthetic or academic concerns, American art became increasingly emotive and expressionistic. Artists began to tell their own stories in their own way, seeking an emotional connection with the viewer and diverging from Classical myths, Academy lessons, and rarefied drawing rooms. The Ashcan School, for example, formed by Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan, and other artists originally trained as newspaper sketch illustrators, portraying ordinary people and evoking gritty scenes of city life. They looked for episodes and incidents affording insight into human nature and contemporary urban life.

As the Twentieth Century progressed, American printmakers became increasingly innovative, devising new techniques and styles to portray the array dizzying cultural juxtapositions they encountered: the Jazz Age and Prohibition, The Harlem Renaissance and rise of the Ku Klux Klan, the Scopes Trial and theories of Charles Darwin, Freud and Einstein, the creation of the Soviet Union and the Red Scare, an economic boom and the ensuing Stock Market Crash. In response, they rendered skyscrapers and sharecroppers’ hovels, churches and schools, main streets, country stores and college towns, big cities and isolated hollows, wheat fields and busy markets, sporting events, vaudeville, automobiles and rushing locomotives. In these new images bread lines and unemployed workers displace wealthy theater-goers on New York City streets, strike breakers clash with police, fields lie fallow and cabins stand abandoned. Nostalgia seemed old-fashioned.

The thirties witnessed further innovations as American artists, striving to reach and attract new patrons and markets, created a body of work representing a multiplicity of techniques. Prints were offered in varied formats, editions, and portfolios at diverse prices. Screen-prints and lithographs, both invented as commercial processes, reached new heights of artistic accomplishment during the period and became unequivocally associated with, and accepted as, fine art. They were less expensive to produce and easily printed in larger editions, thus offering the potential to be more quickly and widely disseminated than traditional intaglio techniques. The “old school” boys’ club network of etching and engraving connoisseurs parodied so often in the prints of John Sloan, Peggy Bacon and many others became obsolete, overcome by technology, ingenuity and creativity.

The range of artists working during the Depression was remarkably democratic and diverse. For example, Grace Albee was born in Rhode Island and trained in Paris; James Allen hailed from Missouri and also trained in Paris. Lucienne Bloch was a Swiss immigrant; Letterio Calapai was a Boston-born son of Italian immigrants. David Chun was born in Hawaii, not then part of the United States, but lived and worked in the Bay Area, as did Chinese-American Dong Kingman. Harold Faye and Reginald Marsh were born to wealth in the New York area. Louis Lozowick, Saul Kovner, and the Soyer brothers were Russian immigrants and also New Yorkers, growing up among former countrymen on the lower East Side. Clare Leighton and Reginald Marsh were British, the latter a native Australian. Georges Schreiber, known for his evocative prints of Midwest wheat-fields, was born in Brussels.

By the 1930s, the United States was already a melting pot. Recently-arrived Jewish artists depicted their Lower East Side environs where bustling markets and picturesque characters were as ubiquitous as silos or wheat fields in Middle America. Allan Crite’s quiet portraits and street scenes depicting Boston’s black community, and William H. Johnson’s spirited, spiritual Southern-inspired screen-prints lent uncompromising dignity to portrayals of African Americans. Women came to the fore. Peggy Bacon, Mabel Dwight and Kyra Markham were the three satirical Graces of American printmaking, and Elizabeth Olds played an integral role in the development of the screen-print. Clare Leighton almost single-handedly revived the art of wood engraving, while Caroline Durieux, Gene Kloss, and others added cultural and ethnic themes to the mix.

In this time of change and crisis American artists supported one another. They joined together to fight fascism in Europe, support progressive political reform in the United States, advocate for social issues or simply sell their work. They understood that sixty patrons purchasing a five dollar print represent the same income as a single painting selling for three hundred dollars. The sale of each edition also creates a potential target audience sixty times larger for their next work. Knowing this, the Associated American Artists produced editions comprising as many as two hundred and fifty impressions. The Depression dried up the pool of rich patrons and American artists were quick to adjust; patrons willing to pay five or ten dollars for a print were more numerous than those able to shell out three hundred dollars for a painting. “The upper class, traditionally the gauge to an artist’s popular acceptance, had all but disappeared as a factor,” writes art historian Bram Dijkstra, and American Scene printmakers looked to the middle classes to help fill the gap.[3]

Many banded together into societies and associations, for example the Contemporary Print Group, the Associated American Artists, or the Woodstock Artists Association. Adolf Dehn created his own successful mail-order print club. They gave up access to the elite for a more democratic audience, posh parlors and portrait painting for popular prints, offering their new public patronage evocative and empathetic images lending local color the gravitas of high culture and the timeless topicality of universal themes, at affordable prices.

Printmaker Alex Stavenitz described the new look in his preface to the American Artists’ Congress exhibition catalogue of 1936: “The exhibition, as a whole, may be characterized as “socially-conscious.” It reflects a deep-going change that has been taking place among artists for the last few years—a change that has taken many of them not only to their studio window to look outside, but right through the door and into the street, into the mills, farms, mines and factories. More and more artists are finding the world outside their studios increasingly interesting and exciting, and filling their pictures with their reactions to humanity about them, rather than with apples or flowers. … This revolutionary change occurring among artists has a complement in the changing attitude of a growing public toward the print. Many are learning to appreciate the fine possibilities inherent in this medium for humor, tragedy, satire, and full-blooded depiction of life.” [4]

Realism had been an integral and conscious part of American art from the Colonial era through the Hudson River School and Ashcan School. Various forms of representation ranging from the meticulous realism of Stow Wengenroth to the stylized urban existentialism of Benton Spruance, or the poetic ambiguities of Dan Rico’s rural industrial scenes, still dominated, in part because these artists respected their audience’s discomfort with abstract or non-narrative forms of pictorial representation. They knew who they were drawing for and why.

In America, aesthetic and formal concerns became subordinate to emotional and human interest. With artists and citizens alike facing extreme hardship, “art for its own sake” became largely irrelevant. Modernist abstraction when employed as an end in itself could appear tangential and inconsequential when weighed against immediate worldly issues, almost as an obstruction to communication. Louis Lozowick, known for his Precisionist, virtually Constructionist, compositions depicting American industrial and urban subjects, characterized the contributions of the American Scene printmakers when he wrote, “If, by a formally significant creative interpretation, the artist fastens the attention of his contemporaries upon a living issue, he continues in the present the work of the great graphic artists of the past.” Artists like Lozowick were determined to be part of the solution, not part of the problem; to delineate graphic narratives which would help describe to Americans their complex new world.[5] Creating art in the service of humanity, Lozowick, Stavenitz and their colleagues were first and foremost visual communicators, translating the world around them to a broad and varied audience of increasingly appreciative and sophisticated critics and collectors.[6]

Social concerns and economic realities transformed American artists and their audience, making them more democratic. Confronted by a harsh reality American artists, many sponsored by the U.S. government, became thoughtful commentators and vivid historical witnesses, creating in a time of crisis life-affirming images of solidarity, humor, courage, compassion and resilience. Their work helped inspire the nation and build a rich, vital legacy of art and history for future generations.

[1] For the full text of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1933 First Inaugural address, and inaugural addresses for all of the United States presidents from George Washington through George W. Bush, see The Avalon Project at Yale University Law School, on the World Wide Web at: (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/inaug)

[2] “Satire in Art,”in Francis V. O’Connor, ed. Art for the millions: essays from the 1930s by artists and administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project. Boston : New York Graphic Society, 1975, p. 152

[3] Bram Dijkstra, American Expressionism: Art and Social Change, 1920-1950. Harry N. Abrams, 20003, p. 19

[4] America Today: A Book of 100 Prints. American Artists’ Congress, 1936, p. 5

[5] America Today, p. 10

[6] America Today, p. 10